Theory? OH No!

I’m finally putting in some musician friendly information. Frustrated with many posts on the net, I’m tired of seeing “information” that either takes for granted that the musician knows a certain amount of background or blows, right through some of the most important facts about how to learn basic theory that I believe will make you a better musician. I like to think all of our students are having to come in through our jam session program. It’s definitely insightful and an educational experience for me. Trying to figure out what’s inside of. Another musicians. Head is frightening by itself. Finding ways to reach, an individual is definitely rewarding for them, as well as myself and future students.

Jumping back between the cord section, and the scale section will definitely help solidify the understanding of how these two structures complement each other.

The best place to learn about music theory is from getting a basic understanding of the Blues Form, since the Blues is the foundation of nearly all the most popular styles of music listened to today. Coupled with performing, it will all come together. This page will be populated with information that will progressively get more difficult. Eventually we will create another upper level page.

The blues originated from a combination of work songs, spirituals, and early southern country music.[2] The music was passed down through oral tradition. It was first written down by W. C. Handy.

Chords

The basic 12 bar (12 measures) blues progression was first published in 1912 by W.C. Handy although the form was evolving for a few years prior.

We usually see the form written down in a chart as so:

C7 C7 C7 C7 F7 F7 C C G7 F7 C C Usually the ending is not a 7 chord because the 7th chord has a sense up an unresolved feeling. You can include a 7 chord at the end if you are going to repeat the form (song) again.

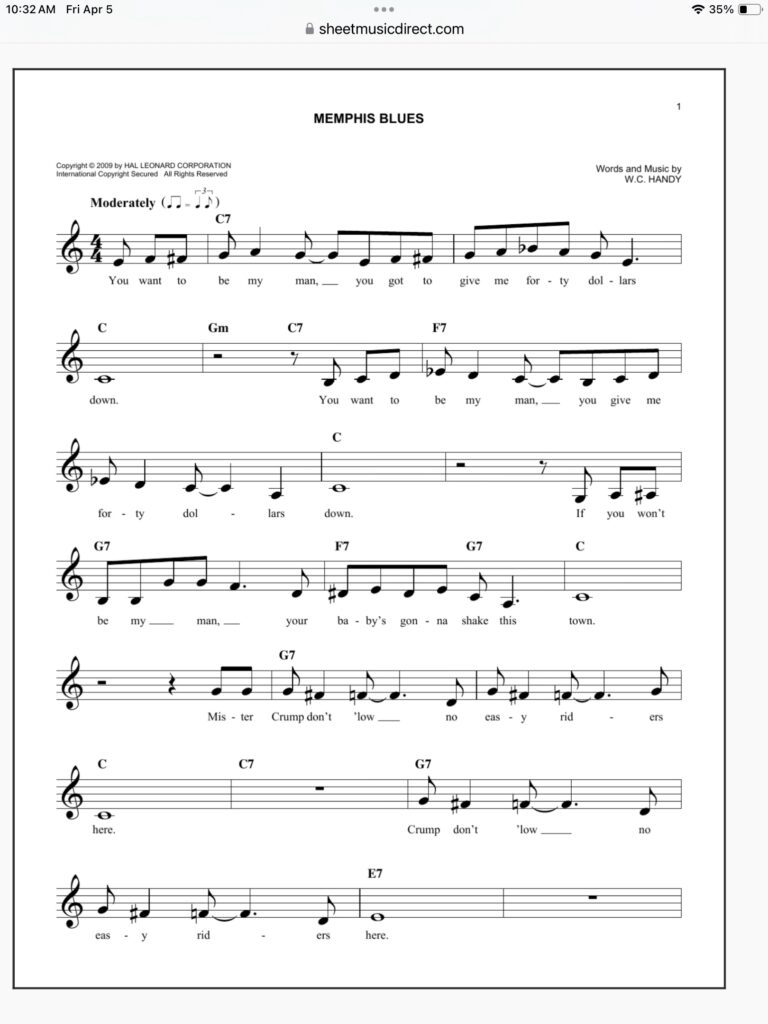

Look at the first half of Memphis Blues sheet and see how close his publication is very similar to a traditional 12 bar.

FROM Wikipedia –

The Nashville Number System is a method of transcribing music by denoting the scale degree on which a chord is built. It was developed by Neal Matthews in the late 1950s as a simplified system for the Jordanaires to use in the studio and further developed by Charlie McCoy.[1] It resembles the Roman numeral[2] and figured bass systems traditionally used to transcribe a chord progression since as early as the 1700s. The Nashville Number System was compiled and published in a book by Chas. Williams in 1988.

The Nashville Number System is a trick that musicians use to figure out chord progressions on the fly. It is an easy tool to use if you understand how music works. It has been around for about four hundred years but sometime during the past fifty years [approximately 1953-2003] Nashville got the credit.

— Patrick Costello[3]

The Nashville numbering system provided us the shorthand that we needed so that we could depend on our ears rather than a written arrangement. It took far less time to jot the chords, and once you had the chart written, it applied to any key. The beauty of the system is that we don’t have to read. We don’t get locked into an arrangement that we may feel is not as good as one we can improvise.

— The Jordanaires’ Neal Matthews Jr.[4]

The Nashville Number System can be used by someone with only a rudimentary background in music theory.[2] Improvisation structures can be explained using numbers and chord changes can be communicated mid-song by holding up the corresponding number of fingers. The system is flexible, and can be embellished to include more information (such as chord color or to denote a bass note in an inverted chord). The system makes it easy for bandleaders, record producer or lead vocalist to change the key of songs when recording in the studio or playing live, since the new key just has to be stated before the song is started. The rhythm section members can then use their knowledge of harmony to perform the song in a new key.

The 12 Bar Blues

The name 12 Bar Blues comes from the number of measures or bars in most blues songs – twelve. Here’s the basic 12 bar blues (Chicago blues) in the key of A.

Further On Up the Road – basic 12 bar blues / A7 /A7 /A7 /A7 / D7 / D7 /A7 / A7 / E7 /

D7 / A7 / E7 /

The ‘Quick Change’

A quick change is just that, changing chords in the 2nd measure and then back the the first chord.

Sweet Home Chicago Chords

/ A7 / D7 /A7 /A7 /

D7 / D7 /A7 / A7 /

E7 / D7 / A7 / E7 /

Blues and the I, IV, V Chords

Many blues songs have just three chords, the I, IV and V chords. In the key of A, that’s A, D and E. Here’s Further On Up the Road by chord name and Roman numerals.

/ A7 / A7 /A7 /A7 /

D7 / D7 /A7 / A7 /

E7 /D7 / A7 / E7 /

/I /I /I /I /IV/IV/I /I /V / IV /I /V/

And the quick change in Sweet Home Chicago? It’s to the …. IV chord …. Right!

/ A7 / D7 /A7 /A7 /

D7 / D7 /A7 / A7 /

E7 /D7 / A7 / E7 /

/I /IV/I /I /IV/IV/I /I /V / IV /I /V/

The Turnaround

1) The last 2 bars of the song ( or more) are called the turnaround. The basic turnaround is

… / A7 / E7 /

2) There are many varations of the turn around. Here’s a common one

… / A7 D7 / A7 E7 /

Quick reference on how chords are constructed from a scale. Further in depth info is will be coming below. below.

When building accordance, we always start with the core name from a particular step in the scale. Let’s use the simplest scale which me a C major scale without any sharps or flats. For each cord we stack notes on top of a particular scale step. Basic cores are made up of the first now third now and the fifth note.

C scale

CDEFGABC

The first note C, third note E and fifth note is G.

CEG = C Major chord

So . . .

G C D

E A B

C D E F G A B C

We now have 3 chords built upon a major scale. C ( the one chord), F ( the four chord) and G (the five chord).

Scales, Oh Crap!

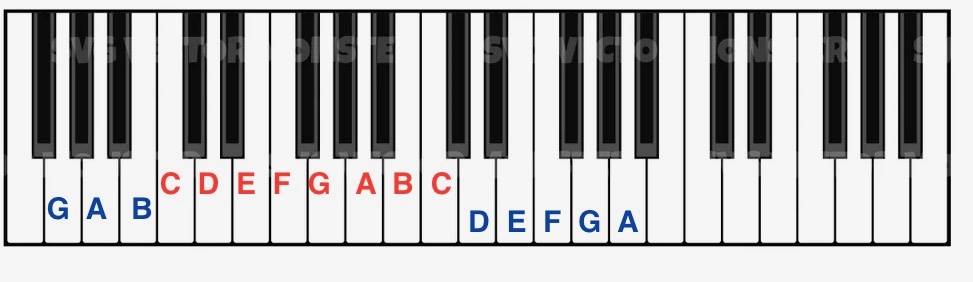

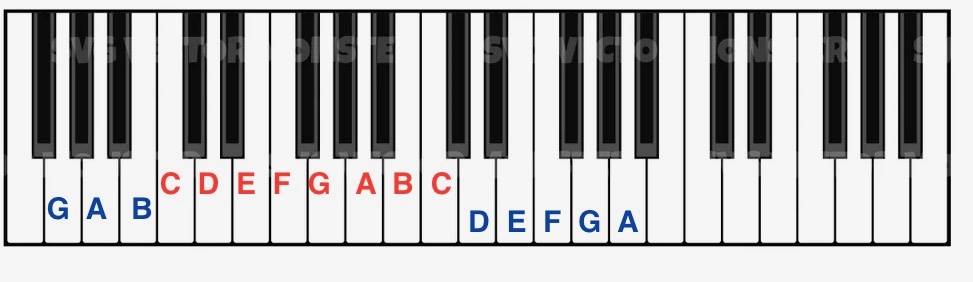

Let’s start with the construction of scales, preferably we will tackle the Major Scale first. It will be a little easier at first when we modulate into how chords are constructed. In the photo I labeled the notes of the C Major scale in Red on a picture of a typical keyboard. As you can see, there are black notes in between some of the letter names, these are usually named a sharp or flat depending on what you call the scale.

Lets skip that for now and concentrate on building a scale using a Defined amount of spaces in between each scale note.

A lot of people have heard of the “whole” and “half” steps used to create any type of scale. If you look at the keyboard diagram, a “half step” means going to the next chromatic pitch. So nothing fits in between a “half step” in western music.

Moving from the C on the lowest note of the C scale, the next step would be the black note in between the C and the D. This is a half step because nothing else can fit between the sea and the black note. So this black note between C and D is called C#( sharp) or it also can be called a Db (flat). Keep these half steps and whole steps in mind for a guitar fretboard. Just moving up to the next fret on the same string is a half step, skipping a fret and going to the next one is a whole step.

The red letters above are a C scale. It is comprised of 7 notes with the first note of the scale, C ending the scale also. So we have a low pitch C and an “octave” above a high C. Eight notes total make up a scale. There has been some confusion “out there” that scales have 7 notes. Wrong. 7 different pitches but 8 notes.

Let’s construct a scale using half steps and whole steps. The formula for ALL major scales is:

W W H W W W H

Starting on C.

Whole step C to D

Whole step D to E

Half step E to F (because there are no sharps or flats between E and F)

Whole step F to G

Whole step G to A

Whole step A to B

Half step B to C (no sharps or flares between B and C also)

Using the formula WWHWWWH, you can now construct any major scale without having memorized what flats or sharps are in each scale. Although, most find when using scales a lot they will be committed to memory anyway in short order. This especial helps when soloing instead of guessing if that note fits within the key you are in.

Statement of fact: you can not use two of the same letter names within a scale unless it is the first and last ( the tonic ).

This will help you understand why in an F scale for example, there is a B flat instead of an A#.

Constructing an F major scale.

F G A Bb C D E F

F to G = Whole step

G to A = Whole step

A to Bb = Half step ( you can’t use A# because you can’t use two letters consecutively)

Bb to C = Whole step

C to D = Whole step

D to E = Whole step

E to F = Half step ( there are no black notes or #’s and b’s between E and F